Millions globally dream of a better future, but for over 2,200 Vietnamese who arrived on the UK’s shores via small boats in just the first half of 2024, that dream is fraught with danger and desperation. Why are so many risking perilous journeys across the Channel, leaving behind a country with one of the fastest-growing economies in the world?

Beneath seemingly prosperous statistics in Vietnam lies a story of inequity—the driving force compelling thousands to escape their homeland.

A Journey of Hope and Fear

Phuong’s story is one of grit and heartbreak. Her harrowing crossing on a small inflatable boat crammed with 70 others wasn’t her first attempt. For two months, she slept rough in French forests, haunted by fear and exhaustion, awaiting her opportunity to board. Torn between terror of the sea and the drive for a better life, she eventually climbed into the overloaded boat.

Today, Phuong lives with her sister Hien in London, an undocumented immigrant haunted by instability. Her sister recounts, “Phuong had no choice. She borrowed nearly £25,000 for this trip. Turning back wasn’t an option.”

Such sacrifices are not rare. Behind these risky journeys is an interconnected web of hopes, financial strain, and exploitative people-smuggling networks.

Why Leave a "Rising Star"?

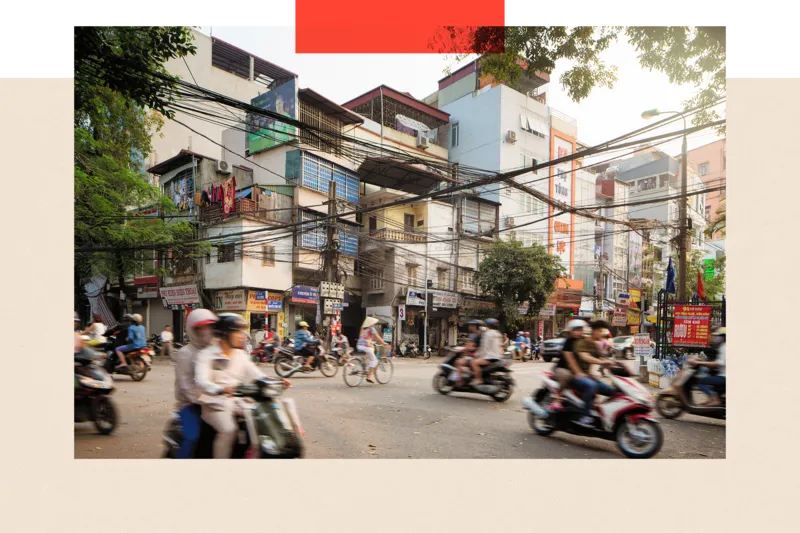

Vietnam is often celebrated as Southeast Asia’s “mini-China,” boasting stunning GDP growth over the last two decades, with incomes eight times higher than 20 years ago. Yet these figures mask stark disparities.

- Economic Inequality

The wealth gap between urban centers like Hanoi and rural provinces remains immense. While Vietnam has reduced extreme poverty, the country’s average wage of £230 per month pales compared to regional neighbors like Thailand. Most of the 55-million-member workforce remain trapped in informal, insecure jobs that offer little chance of upward mobility.

- Relative Deprivation

It’s not always absolute poverty driving migration. Smiling across glamorous social media posts, returnees who’ve worked in Europe beam against the backdrop of palatial new homes in countryside villages, gilded gates sparkling in the sunlight. For those left behind, the contrast is unbearable.

Professor Lan Anh Hoang, an expert in migration patterns, sums it up perfectly, “Two decades ago, people were content with a motorbike and three daily meals. Now, they compare their lives to families receiving remittances from Europe, and they feel poor, even when their conditions have technically improved.”

- Pressure from Home

Vietnamese culture places strong emphasis on family support. Entire families often pool resources to finance the migration of one individual. The burden of expectation—to succeed abroad, repay debt, and send money home—often traps migrants in dangerous business ventures, including illegal work.

The Invisible Costs of a "Better Life"

Enticed by promises of lucrative jobs in nail salons or cannabis farms, many Vietnamese migrants fall into traps they cannot escape. Some are forced into sex work or exploitative labor, contributing to over 10% of modern slavery claims in the UK.

With syndicates painting a rosy picture of success abroad, the risks are often downplayed. Brokers charge anywhere from £15,000 to £35,000 for smuggling routes, with trips detouring through Hungary and other European countries before reaching the UK.

Phuong’s case is a testament to the psychological toll of these undertakings. Living undocumented, without legal status or protection, means a constant battle for survival, even as she dreams of stability.

A Deep-Rooted Tradition

Vietnam’s migration history spans decades. During the 1970s and 80s, the collapse of the state-led economy drove thousands to Eastern Bloc nations, while many ethnic Chinese fled Vietnam’s communist regime, crossing perilous seas to reach the West.

Fast-forward to today, and migration is fueled by Vietnam’s modern-day mantra of success: “Catch up, get rich.” For many, that means seeking prosperity abroad, often regardless of the risks. Lan Anh Hoang remarks, “Money is God in Vietnam. The ability to accumulate wealth anchors the idea of ‘the good life.'”

The Appeal of the UK

But why the UK?

- Existing Networks: Migrants often follow the footsteps of relatives or friends already established in Britain, reducing the feeling of isolation and uncertainty.

- Higher Earnings: Minimum wages and informal work, such as in nail salons or kitchens, offer higher pay compared to equivalent roles back home—even accounting for high smuggling fees.

- Integration Opportunities: Despite challenges, the UK’s multicultural society provides community support that is hard to replicate in other destinations.

Phuong’s sister, Hien, personifies this dream. Smuggled into the UK nine years ago for £22,000, she worked tirelessly in kitchens and nail salons, repaying her debt within two years. Today, she is a UK citizen, living with her family and firmly rooted in stability, a beacon of hope for many in Vietnam still desperate to leave.

Migration as an Economic Pipeline

For Vietnam, migration isn’t just a problem; it’s an economic engine. With an estimated £13 billion in annual remittances, families receiving funds can afford better housing, education, and livelihoods. This “new money” is evident in rural provinces like Nghe An, where once modest homes are now replaced by sprawling mansions.

Despite government attempts to regulate migration through official overseas labor schemes, many prefer the high stakes of illicit routes, drawn by higher Western wages.

Urgent Call for Action

International organizations and governments have repeatedly urged Vietnam to address its pervasive smuggling operations. However, the line between legal labor brokers and illegal smugglers is often blurred.

Without addressing inequality and creating sustainable opportunities at home, the cycle of migration, debt, and exploitation will persist, fueled by desperation and dreams of a better life.

What's Next for Migrants Like Phuong?

Phuong’s story is a stark reminder of the human cost behind those staggering immigration statistics. It’s not just about economics—it’s about hopes, fears, and the universal longing for security and dignity.

For countries like Vietnam and the UK, tackling this crisis requires fostering opportunities at home and enhancing protections abroad. For now, the journeys will continue, as others follow the ghostly trails lit by distant dreams.